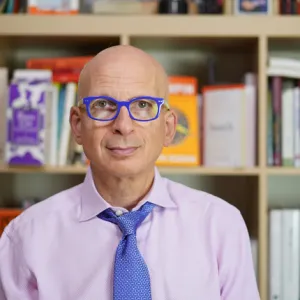

Dan Pallotta

Overcoming Negative Self-Talk and Thinking Much Bigger

First, Pallotta raised millions to fight cancer and AIDS by inventing multi-day fundraisers. Now he’s out to change everything you think about charity — and yourself.

"We have this little voice in our heads that's been talking to us ever since we could understand English," says Dan Pallotta, who's credited with inventing the multi-day charitable event industry. "It's typically pretty punishing, and it tells us, 'You're not good enough. You're not smart enough. You're not capable of achieving your dreams.'"

In this show, Dan shares how he conquered that voice within himself — and helped thousands of others do the same. He also shares why he's taken aim at an even bigger goal: Changing how the entire nonprofit sector views itself.

There is truly no one who has given more creative thought and energy to the idea of doing crazy good turns for others than Dan. More than just an accomplished entrepreneur, Pallotta is an author, an activist, and gifted public speaker. This was a conversation I'd been looking forward to for a long time, and it did not disappoint.

DAN PALLOTTA: Be an NHL goalie. (Laughs.) I desperately wanted to be a goalie in the NHL. I played hockey during the time of Bobby Orr. I was seven or eight years old when he was in his early 20s and in his prime. And I went to Catholic school, where I would pray to God, and say, “Please, please, please, if you let me be an NHL goalie, even if we’re playing out of town, no matter where it is, on a Sunday, I’ll find a church. I’ll go to church.” That’s what I felt was my calling the first time around.

FRANK BLAKE: My first calling was to be a guard for the Boston Celtics, so we share that.

DAN PALLOTTA: And it wasn’t meant to be, right?

FRANK BLAKE: Right. Exactly.

DAN PALLOTTA: Yeah. My dad was a construction worker. But he got involved in volunteering for this campaign for a guy running for the state senate in Massachusets, so I got interested in politics. I was born in 1961, so it was the era of Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy, and John Kennedy, and Apollo. It was kind of a magical time for possibility and leaders who were talking about possibility, and I thought, “That’s what I want to do. I want to be President of the United States.” And I had a path. “I’m going to run for school board, then I’m going to run for state senate, then governor.” Then from there, you can run for president. And that was in the late ’70s and early ’80s. I’m gay. There were not out politicians at that time, and as I began to realize that I was gay, that dream went sailing far away, and so I drifted for a while. When you think about it, we tell kids, “Find the thing you’re passionate about. Find the thing you’re passionate about.” But we don’t have any advice for kids who find the thing they’re passionate about and then society says, “No, you can’t do that.”

FRANK BLAKE: So what was a turning point that got you focused in a different direction?

DAN PALLOTTA: I went to college, started studying Development Economics, and started learning about the massive mortality associated with hunger in the world. 20 million people dying every year, most of them kids, most of it diarrhea. And I just hadn’t been exposed to the scale of that suffering in my middle-class upbringing in Melrose and Malden, Massachusets. And I decided I wanted to do something big about that So I organized a bike ride across America when I was in college. 39 of us rode our bikes across America to raise money and awareness for Oxfam America, and it was a very powerful journey and a very powerful, daunting experience, but a powerful experience.

So then as my life went on and the AIDS epidemic came along, I thought, “The AIDS community needs something more than red ribbons and Saturday morning fun walks. It needs some kind of an epic journey for people to express their love, and their grief, and their passion.” So we created the AIDS Rides — which were long, arduous journeys, seven days long, sometimes across Alaska, across Montana, down the coast of California. Then, we created the Breast Cancer Three-Day Walks, which were these long marches that lasted 60 miles and three days, so that’s kind of the chain of events from wanting to be a goalie to ending up in the center of philanthropy and giving.

FRANK BLAKE: I’ve read that over, I guess about a decade, nearly 200 thousand people have participated in multi-day charity events your company has created. Do you have some favorite stories of participants at your events?

DAN PALLOTTA: Oh yeah. That was part of what was beautiful about it were the stories. Story, after story, after story. See, we didn’t market the AIDS Rides or the Breast Cancer Three-Days to athletes or to cyclists, which was counterintuitive. We didn’t want some testosterone driven, competitive experience, we wanted a beautiful experience of community, and struggle, and journeying together, so we advertised in the mass media, which meant we got the most motley crews of people doing these events. Rear ends of all dimensions, and breathing capacities of all types, and rag-tag cycling outfits, and that’s what made it beautiful. There was this one incredible woman named Susan Silverman, who was going to do the first Twin Cities to Chicago AIDS Ride. She was out training one morning, got hit by a drunk driver, had to have the lower half of her left leg amputated, and I went and saw her in the hospital on the day of the closing ceremonies, and she said, “Next year, I’m going to do all five of the AIDS Rides.” And she did.

There was a woman who was a psychotherapist. Had never raised a dime in her life for charity. She’s now raised over a million dollars for breast cancer year, after year, after year participating in these Multi-Day Breast Cancer events. There’s my mom and my dad. My dad, when he was 64 and we announced that we were going to do the Montana AIDS Vaccine Ride across the Continental Divide in Montana, he said, “I’ve been a construction worker, I always wanted to do something to make a difference in people’s lives, and this is it. I want to do this.” So he spent a year training by himself on the little roads around Malden, Massachusets, and at the age of 65, crossed the Continental Divide twice with me. My mom’s a breast cancer survivor. She and my two sisters walked in the Breast Cancer Three-Day from Worcester to Boston, and when we got to the closing ceremony, her mother was there waiting for her, and she said, “Patsy, I’m so proud of you.” And my mother said that’s the first time she ever heard her mother say that. So the experience lived on that level of spirituality and emotion.

Yes, we were doing it to raise money, and we raised more money than anybody ever had more quickly, but the real power was an emotional power, a spiritual power. That was the prize I always kept my eyes on, was to make sure that we weren’t diminishing that in any way.

FRANK BLAKE: There’s a phrase you use within your company, “Human. Kind. Be both.” And you actively encourage people to experiment, as you say, outrageously, with kindness. What’s outrageous kindness to you?

DAN PALLOTTA: Yeah. That was a great line that our creative director, Rex Wilder, came up with. What experimenting outrageously with kindness means for me is stepping out of your embarrassment and stepping out of your habits, and doing something creative and delightful for someone else. So what we told people on the AIDS Rides is, “Help someone fix their flat tire, even though you know the dinner line is going to get longer. You see someone dragging a heavy duffle bag across camp, offer to help them, even though that little voice in your head is saying, ‘Well, I brought a light duffle bag. Why the hell should I help them if they brought a heavy one?’ Or help someone set up their tent if you see them having trouble with it.”

And people just took us up on that in a big way, and they started to get really creative with it. Going into town and buying big boxes of popsicles and bringing them back for everybody coming into the finish line. A dozen people around someone with a flat tire, so you had trouble fixing the flat because there were so many people there asking if you wanted the help. You know, we live in this rat race, and we’re all afraid that we’re going to get left behind, and I think that makes us very anxious and very desperate, and we forget about love, and enthusiasm, and connection because we’re so afraid that we’re going to get left behind. And kindness, building a community of kindness, helps to mellow that a great deal.

FRANK BLAKE: And is your learning over time that we need events to pull this out of us — and does it stay when it’s pulled out? Or is that it’s capable to find outside of extraordinary events?

DAN PALLOTTA: I still get letters from people saying, “I did the AIDS Ride 20 years ago and it made such a huge difference in my life. It changed the course of my life.” So I think those kinds of experiences open people’s eyes to a possibility. It’s easy to forget, which is why I think we have so many things that are habitual in our lives. We floss our teeth habitually, we eat habitually, we make our beds habitually, but we don’t visit the spiritual side of our lives habitually. We don’t visit kindness habitually. I’ve been in a 12-step program for a long time, and part of the reason 12-step works is I go every week. And I think in business, in the world, people do a workshop one day and they think it’s going to last the next 30 years, or a company brings in a facilitator to do some work on their culture one day, and two years later, the culture has disintegrated, and they blame it on the workshop. Well, you never did anything to keep it alive.

FRANK BLAKE: Yeah, the habit point is such a huge point. And you talk a lot about the potential of people and the potential of society. What do you push in terms of getting people to discover their own potential?

DAN PALLOTTA: You know, you can’t give in to their self-talk, and you can’t let them give into their self-talk.

FRANK BLAKE: That’s a great phrase. What do you mean?

DAN PALLOTTA: We have this little voice in our heads that’s been talking to us ever since we could understand English. It’s typically pretty punishing, and it tells us, “You’re not good enough. You’re not smart enough. You’re not capable of achieving your dreams. That’s for someone else.” So when we started the AIDS Ride, we set a mandatory pledge minimum of $2,000. You had to raise $2,000 in order to go on it, and you had to go the whole seven days, you had to go the whole 600 miles, you had to sleep in a tent every night.

Up until then, these ‘thon events welcomed people with open arms no matter how much or how little they had raised, which was nice and democratic, but it wasn’t a very powerful revenue model. And some people said, “Well, that’s discriminatory. Some people can’t afford that.” And my feeling was, the harder it is for people, the more powerful the experience is going to be.

So I remember this one woman at one of our orientations. She said to me, “Well, what if I can’t raise the money?” That’s your self-talk. What if I can’t? What if I can’t? What if I can’t? And I said, “You will.” “Yeah, but what if I can’t?” “You will.” “But what if I can’t?” “Look, you will. But if you can’t, you can’t go. That’s it. You can’t go.” I said, “But if you make a commitment, you’ll start to inspire people. Why don’t you make a commitment right now that you’re going to do it?” And she did, and I said, “Great. I’m going to give you a hundred bucks. See, if you left here on the fence, I would not have given you a hundred bucks.”

She came up to me on the AIDS Ride six months later, “Dan, Dan, Dan. You wouldn’t believe it.” I think the pledge minimum was $2,000, and she had raised something like $3,800, and she had a completely different experience of herself and of what it was that she was capable of. That’s what I mean. The enemy is inside our heads. Nobody has ever said worse things about us than we’ve said about ourselves. So when you see somebody overcome that, it’s very powerful.

And that’s why I do the work that I do in the nonprofit sector because I think the nonprofit sector has been sold a bill of goods that keeps them thinking very small, and I just love liberating people from that and opening their eyes to the notion that there is zero reason, zero reason you can’t dream as big as Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk. What’s the reason?

FRANK BLAKE: Your TED talk on that point is so powerful in my opinion, so clearly right. Have you seen it starting to make inroads? Or do you just … how do you deal with the frustration of it not being adopted as rapidly as, in my opinion, it should be?

DAN PALLOTTA: There was a Transcendentalist minister in Massachusets who said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” And then Martin Luther King started using that phrase, and it got connected with him. But that’s what I believe. Look, what we’re talking about, what I want to do is change the way the donating public thinks about giving. Stop thinking that low overhead means you found a good charity. Stop thinking that a low salary for the CEO means you found a good charity. Start asking what good they’re doing. When you find out what good they’re doing, whether they’re actually solving the problem, whether they’re actually making a difference in people’s lives, then you know that you’ve found a good charity.

That’s going to take a long time to change that because people have been taught to think that for hundreds of years, so I look at, as I said, I’m gay, I look at the fact that when I came out in around 1980 to my parents, I was 19 years old, they were so depressed. “You’ll never have a family, you’ll never have kids, you’ll never have a normal life. You’ll be ridiculed.” Today, 40 years later, as a result of millions of people coming out and saying who they truly are, I’m married to a wonderful man, we have three beautiful children. My parents, in their 80s, have said that these kids have transformed their lives, and what a thing it is for the thing that you thought was the end of your life, and the end of my life in my 20s, becomes the beginning of yours in your 70s and 80s.

Things change, but it takes a long time, and I think on the arc of changing the way people think about charity, we’re sort of at where gay marriage was at the beginning. But things are beginning to change. Three of the big watchdog agencies, the Better Business Bureau, and Charity Navigator, and Guide Star, about two months after I gave that TED talk, issued a press release telling the public that overhead is not the right thing to ask about, which was like hell freezing over. You now see foundations funding things other than overhead. So it’s starting to change, but I don’t kid myself. It’s going to be a long road.

FRANK BLAKE: And you talk a lot about real social innovation. Is that part of it getting a different framework understanding? The benefits of scale, acting more aggressively towards the problem? What does that mean to you? Real social innovation.

DAN PALLOTTA: Well typically, innovation might mean you bring a new idea to market. The iPhone is an incredible innovation, the iPad, Air Pods, Tesla is a wonderful innovation. What I’m talking about is a more fundamental innovation in the very way we think about charity. As I said, you’ve been taught to think that when you’ve got low overhead, you’ve got a good charity. You’ve been taught to think not to pay people well in charity. But you want the Red Sox to pay whatever it takes to find a pitcher who can win the World Series, right? Why wouldn’t you want the American Cancer Society paid whatever it takes to win the battle against cancer? Why would you think differently about that? So that’s what I mean by innovation there, by really turning upside down this puritan view that we have of charity.

FRANK BLAKE: You told me you’re from Massachusets, I’m from Massachusets. This whole thing started here. When the Puritans came here to sail in the 1630s, and they came here to make a lot of money. They also came here for religious reasons, but also to make a lot of money. But you weren’t supposed to make a lot of money because that meant you were going to go directly to hell, so they had to figure out some way around that, and charity became the answer. I’ll make a lot of money, but I’ll give a little bit of it to charity, and that’ll be my penance for making a lot of money. So we grew up with this religion that charity should be deprived, that charity is the epicenter for self-deprivation, and it doesn’t service anymore. That’s not how we’re going to end hunger, that’s not how we’re going to end veterans’ homelessness. It’s not how we’re going to stop suicide.

DAN PALLOTTA: We need enterprises as big as Home Depot, and Apple, and Coca Cola, but if you tell charities, “You can’t play by those same rules. You can’t advertise the way Home Depot advertises. You can’t pay people the way Home Depot pays people. You can’t take the kinds of risks Home Depot takes. You can’t have access to capital like Home Depot takes.” There’s not a chance in hell that they’re going to ever end hunger, or poverty, or stop domestic violence, or eradicate any of these problems, and we need them to dream at that level. Come on. Apple is dreaming at the level of, “I want to get a cell phone in everyone’s hands.” You, nonprofit sector, you have a right, you have an absolute right to dream your most beautiful dreams and to have the tools and the resources you need to make those come true.

FRANK BLAKE: Speaking of Home Depot, and Coca Cola, and Martin Luther King, as we were preparing to come on for this podcast, you mentioned that you had been in Atlanta last weekend, and then went to Memphis and went to Graceland, and you said you thought there were some interesting connections between Martin Luther King and Elvis. I said, “That’s an amazing thought.” So I want to follow up on that and ask you on-air, what is the connection that you see?

DAN PALLOTTA: Yeah. We took our kids. We go on a road trip every spring, and we did country music and civil rights in Georgia, and Mississippi, and Alabama, and Tennessee this time. And yeah, we went and saw the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and we went and saw the Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King was shot, and we went to Graceland, and the Country Music Hall of Fame. And you know what I found interesting? I don’t want to equate their accomplishments in the world necessarily, but what was interesting is the simplicity of the times. And I don’t mean that in a Pollyanna, Make America Great Again way. They just were very simple times. So Elvis lives in this housing project in Memphis, and there’s this place called Sun Records down the street, and he can walk in the door and for $3.98, record a little record for his mother, and Sam Phillips who runs the place hears it and says, “This kid’s got a good voice.”

Two or three weeks later, they record ‘That’s Alright,’ and within six weeks, this kid who was living in a housing project has international fame. That’s what I mean by the times were simple. So he became very famous at a young age. Martin Luther King as well. He took the pastorship at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery at a young age, I think he was 24 or 25. He was just looking for a simple place to finish his dissertation and pastor a parish, and little did he know that the bus boycotts were already in the works and he was asked to lead the Montgomery Improvement Association and found himself in the center of the Civil Rights Movement and on the covers of magazines. What I found interesting was geographically how closely they grew up to one another. The time, it was the late ’50s, their early meteoric rises to international celebrity. The fact that they both died in Memphis. The fact that they both have water features around their graves. I just thought it would have been interesting for Elvis and Martin Luther King to be high school friends. I wonder what they would have talked about, you know?

FRANK BLAKE: That’s a really interesting question, and I’ll just do one odd segue from that to another thing you’ve talked about, which is the idea of love. Of its power and how you see the destructive side of it. Like in some of the infighting you’ve seen in communities like nonprofits, “in the name of love.” What have you learned about love, how people love one another, and what we can do to be more effective in channeling it?

DAN PALLOTTA: I think we’re mostly driven by fear. Philanthropy comes from the Latin philos anthropos, love of humanity, so in the nonprofit sector, we think we’ve got the love thing down way more than corporate America. I don’t think that’s true because we have all kinds of things that distract us. We have people that we don’t like. We have job security issues. We have office politics. We have budget realities. All kinds of things that distract us from love. When I was in high school, I was a big John Denver fan. When everybody else was listening to Zeppelin and Jethro Tull, and I just loved the bells of his acoustic guitar and the way he played it. And he used to credit Warner Erhard and everyone in EST on his albums. And I thought, “What is this thing? Because he’s got a different sensibility about it. It must have something to do with this EST thing.”

So I wrote to him, and he sent me back a brochure. And my first weekend at Harvard, I did the EST Training. Lots of celebrities were doing it back then, and people were calling it a cult. It was on the cover of magazines, and it was a profound experience and enlightenment for me. It was like getting zen enlightenment over the course of two weekends. I don’t know how they constructed it so you were able to have that experience, but you saw the commonality in human beings. You saw that self-talk that I talked about earlier, that we all have this self-narrative that badgers us, and punishes us, and makes us suffer all day long, and we don’t appreciate that we’re all dealing with that. And I began to see at that early age that this is the answer.

We’re looking to politics for the answer, but the answer lies in the domain of being. Why isn’t Congress in some kind of a conflict resolution workshop four times a year? Why aren’t they in therapy? Why aren’t they on retreat regularly? Businesses work on their culture. Who works on the culture of Congress? Nobody. There’s no department of culture for Congress, so you have this horrible culture and we wonder why. Well it’s because we don’t put any energy or effort into it. If I didn’t put any effort into the culture of my family, I would have a horrible culture in my family, but I put a lot of effort into the culture of my family.

So we’ve got our eyes on the wrong prize. It’s like, “Well, who can win next? Who can win next?” One of the reasons I’m actually excited about Marianne Williamson, who I used to see lecture all the time on a course in miracles because she’s enlightened. It’s amazing and wonderful to see a semi-serious — because she could be in the debates if she gets another 8,000 donors — contender for the presidency who is talking about these kinds of things. About love as the foundation for what we do. I don’t know how old you are, Frank. I’m 58 years old, you’ve been alive for 58 years, you’ve seen the pendulum swing back and forth enough to know that it doesn’t really matter who gets elected. It’s just going to be the same damn thing over and over again. The left will have power, the right will have power.

There’s a different domain where we need to start looking for the answers, and to me, it’s love. And love in a rigorous way. Because love can be sweet, and kind, and nice, and that’s nice, but sometimes that can be backstabbing when you’re being nice and you really hate the person. I think bringing the kind of rigor of responsibility for your own thoughts, communication, and perspective — that’s what love really is to me. Being rigorous about your judgments about other people, about the prisons in which you put other people in your mind. That’s what real love is.

FRANK BLAKE: That is brilliant. And I have to say, having served in government, your comment on the culture and the need to pay attention to the culture, that needs to be your next TED talk. People need to listen to that and change. So Dan, final question. You do a lot of writing, you talk to lots of different groups. Where’s the best place for interested listeners to find out more about you?

DAN PALLOTTA: Simple. Just go to DanPallotta.com. If you go to DanPallotta.com, you can find out about the books I’ve written, speeches I’m giving, the Bolder Board trainings that we do for nonprofit boards. I just wrote this fun little piece of humor, a rant about flying and God called Sky Problems, so you can learn about all that stuff at DanPallotta.com.

FRANK BLAKE: Perfect. Well, thank you again. This has been a great privilege.

DAN PALLOTTA: Fun conversation, Frank. Yeah, thank you.

I'd love to hear your thoughts after listening. You can share them with me in the comments below, or by emailing me at hello@crazygoodturns.org.

- Dan Pallotta Website

- 2013 TED Talk: The Way We Think About Charity Is Dead Wrong

- 2016 TED Talk: The Dream We Haven't Dared to Dream

- Charity Case: How the Nonprofit Community Can Stand Up For Itself and Really Change the World

- Uncharitable: How Restraints on Nonprofits Undermine Their Potential (Civil Society: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives)

- Sky Problems: A Frequent Flyer's Encounter with the Astral Plane