Nellie Bowles

Courage and Controversy

The former New York Times journalist risked her career and friendships alike by asking questions about some of the most controversial subjects of our time.

Our latest guest Nellie Bowles risked her

career, and her friendships, in pursuit of honesty.

By doing so, she created a voice for the increasing number of people who prefer

open-mindedness over advocacy.

Bowles wrote for the New York Times from 2017 to 2021, receiving several awards for her writing.

While at the Times, she engaged with some of the most contentious issues roiling society at the time: The George Floyd protests, Defund the Police, DEI and so on.

Her writing on those topics, I would say, was

fundamentally sympathetic toward the point of view of those protesting - but

also clear-eyed about where these movements may have gone too far.

And it was that act - remaining clear-eyed, and

continuing to ask questions when she was told not to - that was viewed by many

in her circle at the time as "betraying the tribe."

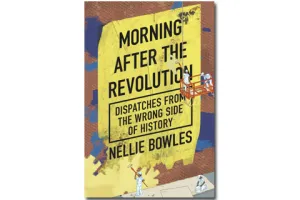

Nellie ultimately left the Times to launch what is now called "The Free Press" with her wife, Bari Weiss. And she documents her journey in her new book, "Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History."

It takes courage to engage with controversial

topics, and even greater courage to be willing to do so with an open mind - not

merely seeking to support your already-held beliefs.

I truly think there's a lot we can learn from Nellie and her story, and I'm excited to bring it to you.

If you enjoy this episode, sign up for a chance to win one of 50 FREE copies of

Nellie's book.

It's a humorous and insightful description of questioning where you thought you

belonged.

Click here to enter to win your free copy.

You Can Help Others Doing Great Work

Last year our podcast donated $50,000 in grants to organizations who are helping others, including three groups news to the Crazy Good Turns family - Just Keep Smiling, Hearts and Hooves Corral, and Joshua's Place.

This year, we are again looking for those who might not be in the spotlight — but who are changing lives for the better. And we are relying on you, our audience, to highlight them.

Your personal recommendation could lead to an organization being featured on our podcast, and receiving a $10,000 donation.

- Nellie's definition of revolution, and what drove her to write her book (5:07)

- Her work for "The Free Press" today, and how it and other publications like it open up new avenues for journalists and writers (22:15)

- A surprising thing that objectivity and kindness have in common (10:51)

- A childhood mentor who set Nellie on her path and helped her become who she is today (30:02)

FRANK

BLAKE: Well, Nellie, this is a real privilege to have you on the show, and

congratulations on your book. It's terrific.

NELLIE

BOWLES: Thank you so much.

FRANK

BLAKE: I have to start with a story, which is, my sister was visiting here from

London just a couple of days ago.

And she's a writer, she's written over 12 books and she's done well writing.

And she sits down and she sees your book and she picks it up and she reads it

and she reads it cover to cover. And afterwards she puts it down.

And actually, I'm going to have one question from her in this interview, but

she puts it down and she said, "Well, tell her she's a really good

writer."

And for my sister, that's high praise, so congratulations.

NELLIE

BOWLES: Thank you so much. Tell her thank you.

FRANK

BLAKE: Yeah, it's a great book. It's a well-written book.

And I love, early on, I think in the introduction, you have a quote saying,

"My ideal reader feels a little tribe-less, a person of curiosity whose

politics are more exhaustion than doctrine."

That has to count for a lot of us. Could you explain where that comes from as a

description of your ideal reader?

NELLIE

BOWLES: It comes from trying to describe myself a little bit.

In the book, I document the change both happening in society over the last four

or five years and also within myself.

And part of that was going from being someone who's kind of an ideologue or at

least very committed to being along with one party, to being someone who felt a

little out of sorts with that and felt a little not connected to one ideology

and one right answer.

And I think that a lot of Americans are feeling that way and looking at the

left and the right and thinking neither of these things really describe me

quite right.

Neither party feels like the perfect home.

And most people aren't as flat as our current political moment would have us

believe. Just simple.

Their politics aren't every single plank of the most progressive agenda or nor

are they every single plank of Trump's agenda.

It's a messy mix of a lot of ideas and a lot of opinions, and just being

comfortable with that and being, as a writer and as a journalist, being okay

with not being on an ideological crusade necessarily.

FRANK

BLAKE: So I love the subtitle of your book.

The title of your book is The Morning After the Revolution, the subtitle is

Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History, which I guess is a reference to what

one of your editors at the New York Times told you.

Would you describe a little of the background to that?

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah, so when I first started doing reporting in 2020 and 2021 on some

of the things that we weren't supposed to cover, which for those years was a

lot of things, and it happened to be the most interesting stories in America

were sort of off limits.

Like a lot of what was going on in American cities with ANTIFA/BLM protesters

making these autonomous zones where they would take over a few blocks and claim

it as a new city or just tons of different stories that were happening that we

were basically all in lockstep supposed to not cover and ignore.

And that was really hard for me, and I ignore it because covering it would've

been helpful for Republicans, would've been helpful for conservatives.

FRANK

BLAKE: "Other side."

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah.

And the project was you don't want to give them fodder and why would you want

to embarrass the movement when there's a lot of good, and sure there's some silliness,

but we need to ignore it because we don't want to give fodder.

That was really the argument. Not that it's not happening, but that it's not

useful to cover so we should not cover it.

And that just didn't sit with me.

So how that pushback happened within the Times was really socially. It was

other colleagues and some editors.

My boss was actually pretty amazing, and a lot of the bosses at the Times found

themselves somewhat flat-footed in this moment and we can get into that, but it

was mostly collegial where the colleagues would police you and say, "We're

not covering that," and, "Why do you want to cover that?"

And I

had someone say, everyone I described in the book, there's basically five of

them in reality.

This was based on one conversation, but I had this conversation with a million

people.

But yeah, I had someone say to me, "I don't know why you want to put

yourself on the wrong side of history."

And when I look back, I want to look at my work and know that it was good for

our movement, it was good for this march of progress. And why would you not

want that?

And I was kind of dumbfounded by the conversation. It really stuck with me.

And after I went to one of these zones and reported on ANTIFA and all the

hilarious, absurd stuff that was happening, also crazy and there were shootings

and it was really rich stories.

When I

came back, basically my colleagues decided I'd crossed the Rubicon and so they

start tweeting out things, how I'm a fascist and a this and a that.

And once you violate the law within one of these... And the Times is the same

as Washington Post, same as NPR, all of these organizations have the same set

of rules, basically.

And once you violate that, you're really on the outs.

And you'll see, the group of somewhat dissident Times reporters of that era, a

lot of them have slowly left, a lot of them spread out into other news

organizations that aren't as mainstream and dogmatic.

FRANK BLAKE: I imagine that as you're going through this, there are choices, right?

You have a choice.

You can kind say, "Yeah, okay. I love my job."

As I understand from your book, this was absolutely your dream job. Okay, there

are some things, I'll just cover the things that seem to work and no harm, no

foul.

What kept you from doing that?

NELLIE

BOWLES: Well, I have a kind of contrarian personality, like a little bit of a

rebellious personality.

As a kid, I was always described as having trouble with authority figures.

And it was actually that trait that made me love journalism, because journalism

was the job where people who have trouble with authority figures get to get

that energy out.

It's like running around a track or something. I got to have a lot of trouble

with authority figures and it was really fun for me.

And that trait just made it impossible at a certain point for me to go along

with it.

Not to

say that I didn't go along with a lot of these new rules for a while, and I

really did, and I was very good at it for a while.

But it became harder and harder. It just became impossible to not be curious.

And then once I sort of got the feeling of rebellion in me where I was like,

"You guys are going to tell me I can't do this?"

Then I became obsessed with it. It was all I wanted to cover and it was all I wanted

to think about.

I was like, "The revolution is everything," and I just couldn't stop

myself.

FRANK

BLAKE: How I think of what you have done with this book and elsewhere is part

of the crazy good turn is, it's not like you are trying to play gotcha with one

side. It's just, I'm going to tell you what's going on here, whatever the

consequences are.

Which one might've thought of as sort of the core of journalism, but I guess is

not so much anymore.

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah.

I think that the old idea of objectivity or even objectivity being always

something that's an impossible thing to be. You can't be objective, but the

idea was we would try.

And we would try to keep our eyes open and keep our minds open and be curious

and responsive. Again, knowing that objectivity is impossible.

It's like saying kindness. We all want to be kind, but no one is perfectly

kind. And that ethos, I liked it. I think it's very good. I think it's a really

good ethos for reporters to follow.

And so when it got lost and when everything became about just this sort of

basic boring ideology, it's just boring as a writer more than anything.

And I

think about it with... So venture capitalists always try to say that the tech

press is too negative and we're going to start our own. And they're right, the

tech press is often too negative.

But when they start their own, it ends up just being on-staff writers for

Sequoia Venture firm and it's boring. And so no one reads it.

And when you're writing propaganda or puff pieces, it's boring.

It's that the Times and the Washington Post and a lot of NPR, a lot of our

mainstream institutions have handcuffed themselves and said, "We're not

going to look at these stories. We're going to intentionally make it boring to

our readers and to our writers."

It's astonishing.

FRANK

BLAKE: But the flip side of it is that the penalty for going outside the tribe

is pretty high.

It's not like people go, "Oh, okay, well, Nellie's straying a little bit,

we'll try to reel her in."

It's a pretty violent response.

NELLIE BOWLES: Yes. A dissident liberal is the most dangerous thing for the

movement.

So if I was like, "You know what? I'm a conservative now. I'm voting for

Trump and I'm this and that," then it would be fine.

And actually, sort of-

FRANK

BLAKE: She's lost her mind, let her wander in the desert.

NELLIE

BOWLES: But to have someone be like a dissident within the world of liberalism

broadly is very dangerous.

And so the movement, I don't have any tiny violin to... We're great, we're very

lucky. Everything turns out well.

But the movement obsesses over these dissidents and obsesses over destroying

their lives basically.

So you see this with a lot of it is academics who really can't function outside

of an institution. There's no secondary market for an academic where they can

go direct to consumer.

And so you see their lives get destroyed when they question things. When they

say, "Oh, let's study biological sex and talk about this or that."

Stuff

that used to be considered completely normal, now their entire careers are

destroyed and there's no second place for them to go to use that training.

So the culture of fear is very real and justified. And for a lot of people, the

cost is too high.

And I think with journalism we've been really lucky because we can go direct to

consumer.

FRANK

BLAKE: Yeah.

And did you wrestle with the decision on whether, I mean, two separate

decisions. Leaving the New York Times and then publishing your book.

Did you wrestle with publishing your book and say, "Oh wow, I know this is

just going to bring on a lot of anger?"

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah, I did. I tried to do it in a classy way.

I mean, I didn't name names, I didn't throw any particular editor under the bus

and I feel good about that. And of course I wrestled with it.

Because also there's a lot of great people at the time, so I don't want it to

be like, oh, the whole place is gone. Because there's thousands of reporters

there and the vast majority are great and do want to do great work.

It's just a small ideological faction that's managed to gain a huge amount of

control of all of American newsrooms. But the vast majority are still normal

people who want to do reporting.

So I also wrestled with that aspect. But yeah, making the choice to leave one

of these institutions, it was really hard.

I was a

mess about it. It took me months.

I lost real friends by doing it. I lost real friends by doing the reporting I

was doing there. And I mean, it was almost formal in how it was done. They

would write me and say goodbye basically.

And there was one time when I really

crossed the line, which was we were all supposed to cancel a young editor and

say that this piece that the Times had published put our black colleagues in

danger.

And I knew that young editor who had edited the piece, and I just didn't

believe it put our colleagues in danger. And so I didn't tweet out the tweet.

This sounds so dumb. And for listeners, if this sounds crazy to you, it is

crazy and it is so pathetic. But we were all supposed to tweet out this one

message and I didn't.

And

that day I got texts from a bunch of friends, but from real people in my life

who said, "If you don't write this, you're not standing with us. You're

not showing solidarity with your colleagues who are saying we need you to post

this."

And I just couldn't do it. And so after that, then it was really done for me

within the movement.

And it didn't help that throughout this, I then started dating another

dissident reporter or writer at the Times.

So then it became sort of like I was dating this woman who was also a dissident

liberal who was also writing these bad things. And then it was really, then I

was screwed.

It was over. I knew it was over. But it took me a while to get there in my

mind.

And in part because a lot of the leadership of these places, the Times, among

them, they don't want this movement to win. They're trying to push against it.

And so they were saying, my wonderful editor was saying to me, "Stick

around. It's fine. We're going to get this moment will pass," and all this

stuff.

And I just didn't believe that that was true, at least not for like a decade.

And I

didn't have a decade to sit around and be doing internal memos, trying my best

to improve. I think there's a beautiful space for people who want to do that,

and that's really important work also.

And I know there are a lot of people in these institutions working to improve

them from the inside.

But as a very selfish person, I just was like, "I don't have time for

this."

I can't spend a decade devoted to internal machinations to try to slightly

improve an old institution that really didn't want to be changed in those

years.

And I don't think even now.

FRANK

BLAKE: So here's the question from my sister on your book. What's been the

reaction of your friends and colleagues?

NELLIE

BOWLES: My friends and colleagues now are people in the new world.

FRANK

BLAKE: I guess a divided kind of reaction.

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah, it's been really positive. It's been super, super positive.

The old one, the Times, the Washington Post, and the New Yorker ran brutal

reviews. And I was sort of shocked and also delighted by it because it really

aroused so much anger in them.

I mean, normally when these places don't like a book, they just ignore it.

But for me, they were blasting it out as the most important review written

ever. And these were just slams, just brutal slams. Bad writer, boring topic,

old news, all this stuff.

And I don't know, it was kind of funny to me now to see the focus on it. That

they couldn't ignore it was to me a win.

And then the book ended up making the Times bestseller list, which was one of

the sweetest moments of justice. I was embarrassingly excited even as I was

trying to pretend I didn't care at all.

FRANK

BLAKE: Can I ask you, as you reflect on it, what do you think it counts for,

the lack of self-awareness?

Or maybe at some levels I go lack of a sense of humor or a sense of perspective

on life? How can this be?

NELLIE

BOWLES: Well, the movement and the people in it, the NPR and Washington Post

and New York Times, does not believe that there's anything funny going on.

And to point to humor is to, first of all, like I said before, give fodder to

Republicans. It's to give fodder to critics.

And the stakes right now are so high and there's nothing to laugh at in this

situation. And so humor is really problematic in that world. It's really hard

for them.

I feel bad for them because it seems boring to live like that.

But yeah, it's why I like stand-up comedians. They're obsessed with canceling

random stand-up comedians stand-up. Comedians are offensive. That's the whole

job of the stand-up comedian.

FRANK

BLAKE: Well, so if you look at the reviews from your former colleagues at the

Post and the Times and all the rest, since the title of your book is the

Morning After the Revolution, do you go, "Wow, this revolution's not

over."

There is no break in the fever here.

People are even just as committed as they were even as a little bit of a return

to rationality has happened in places like San Francisco and Seattle and the

rest.

NELLIE

BOWLES: I think that the heat of the revolution has somewhat passed.

I mean obviously it has, right? Our cities aren't burning and a lot of the most

egregious policy ideas are being pulled back.

You don't see much outrage over the return of the SAT, which for a few years we

were told that the SAT is for white supremacy.

I could ramble about that for a while, but you definitely see a pullback from

some of the more embarrassing fringe arguments.

But I think as the heat has wound down, it's in part because of the movement's

success.

It's because the movement has so successfully won in so many of our institutions.

So the revolution's ending, but it's not leaving us in the same place where it

began. It's leaving us in a new place where a lot of wins have been made.

I mean, I think about there's this Columbia student who said in a video that he

ended up later posting himself, but he said to a group of administrators who

were meeting with him to talk about some punishment for something else he'd

said, he said, "I want to kill Zionists and you're lucky I'm not killing

them right now."

And he

said that to a group of Columbia administrators, a group of professional adults

within the university who have the authority to punish this guy.

And he wasn't punished, and it was completely an okay thing to say. And he

walked out.

And the only reason that we heard about it is because he posted the video of

him saying it himself to that group because it was like some sort of panel done

on Zoom.

And then once the video went viral and there was outrage, then the university

said, "Oh my gosh, we have to suspend him. We're going to suspend

him."

But to me, the most important part of that little moment was that he had said

it to a group of administrators at Columbia University, an Ivy League school,

and he hadn't gotten in trouble.

So that

tells you that something has shifted within the institution where that's

allowed.

And just I think that in many of our institutions now, there are conversations

and demands put on people and put on students that are really, really different

from five years ago.

And so you can't say that just because the police weren't abolished that the

movement didn't win.

FRANK

BLAKE: So that is a great way to segue to the Free Press and what you're doing

there. I follow the Free Press, I read everything you guys write and you're

really clever and thoughtful.

Maybe a little bit of the story behind that and how that is going.

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah, so the dissident writer I was dating at the Times, she quit

before me in a kind of fiery splash. That's a bad metaphor, a fiery splash.

And she had this idea for a new media company.

And the original idea was it was going to be a huge media company with all

these different branches, and I was more of a practical, I call it like a

weasel mind.

I was just like, "Let's start a newsletter. Let's start a really basic

thing and just collect some email addresses for now."

And so I set up bariweiss.substack.com of course, screwed up a million things

including just like the URL, why did I choose that URL? I don't know. But it

caused all kinds of problems.

I was doing our accounting for the first year, it was a mess.

But we started this little newsletter that was mostly, I mean, she was an

editor and opinion writer and pulls together different voices and is a genius

at curation.

And so she started curating all of the different dissident people and building

the Free Press. And we've just seen it grow and it's been amazing.

FRANK

BLAKE: Well, it's a terrific product is where I would start, is the podcast is

terrific. The writing is terrific, and it's honest.

It's very honest reporting and opinion pieces.

NELLIE

BOWLES: I think that because of all the stories that are not being covered,

there's just a lot of low hanging fruit.

And so it wasn't even that hard to find all these different beats that we could

just own and very easily and just start writing about and it would be

considered wild and shocking.

I mean, we were writing about puberty blockers when that was considered

verboten in mainstream media.

And turns out a lot of parents wanted to know a little bit more about what was

going on with all that, or writing about COVID origins or writing about just

all these different things that are so interesting.

And so the publication grew and it started making my partner slash now my

wife's salary, it started making her old salary at the Times. And then it made

double her salary at the Times.

And I was just watching this, like holy shit. I was looking at the line and I

was like, this might be a company.

At the

time I thought, oh, I'll leave the Times and freelance for other magazines.

And then I was like, no, I'm going all in. We're all in on the Substack. And

it's just been amazing.

It's been so joyful and positive.

And it's become a refuge for a lot of people from the old media to come and use

those skills, use the reporting skills.

One of the first hires we made was a fact-checker and a copy editor, someone

who makes sure our facts are really good and tight.

We have the standards of the old world, but trying to have the mindset of the

new, which is just more open-minded.

But I think one of the things about the new world that's risky is without the

institutions and the guardrails, it's hard to keep your bearings. Think about

COVID and stuff.

And you see a lot of people who started questioning COVID and some of the lies

the government was telling us then spin out too far and start believing any

conspiracy theory they see. You have to kind of guard yourself.

And one thing that I think we've been trying to do with the Free Press is build

a community that is its own little institution rather than just we're all

free-floating bloggers online kind of posting whatever comes to our heads.

But it's been great.

I think about when I was thinking about leaving the Times and how scared I was

and I asked all these people for advice, and I mean my parents are supportive

of whatever we want to do and sort of amused by the chaotic antics we all get

up to, my siblings and I.

But I

think they were a little bit shocked that I would leave the Times and

especially a place like a Substack, what is it?

I just feel so grateful that I took that risk.

But it was also an easy risk to take in a lot of ways because I was young,

healthy, no kids. It's an easy time to take risks in your life.

I think now, I'm still youngish and healthy, but I have kids.

I think I'd be a little bit more scared of taking a risk.

Which is all to say, I understand why a lot of people don't just quit a bad

institution and say, "To hell with it," because it's hard to do that.

FRANK

BLAKE: there's a line in your book about not being able to unsee complexity.

And that strikes me as one of the things you all are doing with the Free Press,

is you're showing people some of the complexity and it's so much more

interesting seeing the complexity. Where do you see the Free Press being

three to five years from now?

NELLIE

BOWLES: for a while I was so scared because I thought, well, if the New York

Times and Washington Post decide to be 5%, 10% less crazy, they could take our

business.

If they decide to start reporting on some of these stories, oh my God, we're

done.

And they just haven't made that choice.

And so I see the Free Press growing. I mean we've been growing, and I'd like it

to be a new American institution that is a home for people who want great

stories, great writing, great reporting.

I want us to do more events, I want us to have more beats. I think early on we

were focused a lot on the thing that Bari and I were both coming from, which

was internal battles within Liberalism.

And so

early on that was most of our coverage was about, the internal battle within

liberalism.

And I think now we're trying to branch out and we want to have beat reporters

who cover things on the ground and bring breaking news and things like that.

But keeping it sustainable and keeping it... I mean, one thing that we're very

lucky on is the timing for starting a subscription business was very good

because ads have crashed.

So ad-based businesses are a mess. And subscribers, I like writing for

subscribers.

I like that as a structure. And so I see us growing in that and making a better

and better newsletter every year.

FRANK

BLAKE: So not related necessarily to the Free Press, more general question.

Who in your view isn't getting enough attention today?

Who should our listeners be paying more attention to?

NELLIE

BOWLES: Well, I'm really biased, but I would say that the writer Abigail

Shrier. She is one of our good friends.

And she was very early on the issues around teen girls and gender dysphoric

contagion.

So sort of how a lot of otherwise healthy teen girls spend a lot of time online

and convince themselves of different esoteric gender identities.

And she was very early to say, "We should just give them a minute to think

about things before we medicalize them. This might not be exactly what we think

this is."

And she wrote a book on it and it was great. And she was early.

And she's someone who I think about a lot. Like you asked me, the revolution

ending.

Abigail

Shrier never got apologies from the people who smeared her as a transphobe for

writing that book.

Even as now, the things she was arguing a few years ago are literally the law

of the land in England, literally the law of the land across Europe at this

point. She never got vindicated or apologized to.

I just think she's so brave, impressive, and people should go back and read

that book.

And her new book wasn't number one on Amazon and blah blah. She's certainly

extraordinarily successful.

She's not an under known, little known writer, but her last book was just very,

very brave and she's very, very brave.

FRANK

BLAKE: So I ask this for everyone who's on the podcast.

Who is someone who's done a crazy good turn for you?

NELLIE

BOWLES: I would say, I went to a little boarding school in Southern California

and my dorm head/advisor ambiguous role, his name was Bob Bonning or is Bob

Bonning.

And he completely made me the person who I am. I arrived as a really

rebellious, angry 14-year-old. My parents had gone through divorce.

I was sort of pissed off at everything and he just took me under his wings and

was this curmudgeonly funny guy with a goatee who would hang out outside the

dorm and have a cigarette and then come back and tell us what to do and all of

this.

And he

really saw who I was very young, and embraced it and let me be who I was.

And so I wanted to do the school newspaper and I didn't want to play lacrosse.

I didn't want to play team sports, and we all had to play team sports at

school, but he kind of let me sneak off and not do team sports and instead just

do the school newspaper all afternoon.

He was the first person who told me that he thought I was a writer and that I should

probably do that.

But he told it in a curmudgeonly way. "You're writing a lot, they say it's

pretty good. You should probably look into that."

Very low-key and dry and just very accepting of a little rebellious teen

version of me, which was really fun.

FRANK

BLAKE: That's awesome.

NELLIE

BOWLES: He would be embarrassed by how I'm describing him.

FRANK

BLAKE: No, that's good. That's terrific.

NELLIE

BOWLES: I've written him many thank you's over the years.

FRANK

BLAKE: Well done.

NELLIE

BOWLES: Yeah, he was very influential in my life.

And I think anyone who wants to do stuff that you can't fully buck a community

if you don't feel safe somewhere else.

And because of my family and people like Bob Bonning, I felt very safe in a lot

of ways in my life.

And so it felt okay to say goodbye to a place like the Times and to the old

world prestige and to say, "You know what? I don't need it."

And that's okay because there's a lot of people in my life who love me no

matter what, and I have a lot of safety in other ways.

And yeah, I think that was essential to be able to take risks in professional

ways.

FRANK

BLAKE: That is fantastic. That is terrific. Well, he is much to be thanked.

And thank you, Nellie. This was terrific.

Your book is awesome and I encourage all of our listeners, we're going to be

giving away copies of your book, and I also encourage all our listeners to

listen to the podcast and read the Free Press on your Substack.

And one final question that just occurred to me is we're signing off on your

book.

So if someone buys your book or gets this book as part of our podcast, to whom

would you recommend that they give the book after they finish reading?

NELLIE

BOWLES: I would say give it to sort of your coolest young cousin or grand cousin.

Someone who might read this and have their mind changed or opened a little bit.

I think that would be a good person to give it to.

FRANK

BLAKE: That is perfect. Well, thank you again, Nellie. This is really a

pleasure. And again, congratulations on your book.

NELLIE

BOWLES: So much. Thank you for having me.

Enter to Win a FREE Copy of 'Morning After the Revolution'

In this New York Times bestseller, Nellie chronicles her evolution from devoted progressive to one who feels politically homeless during and after the social upheaval of 2020.

Click here to sign up for your chance to win.

Secure a Major Gift for a Cause You Care About

Selected causes will get the chance to be featured in an upcoming episode of our podcast.

Nominate yours HERE.

From Frank Blake

My Sincere Thanks

Your support has helped take our little idea to celebrate generosity and good deeds, and turn it into one of the most listened-to podcasts available.

Thank you for being part of a community that celebrates people who do good things for others.

Your giving of your time to listen to these interviews, and acknowledging those good deeds, is a crazy good turn of its own.

Please help us continue to grow by subscribing on your preferred podcast platform.

And please, help us spread the word by sharing our show and website with friends.